I don’t write much here at the moment because when I’m back in the classroom, I have very little mind space to sit and let creativity in. I am very much on the struggle bus right now and just trying to get through the days. But, a slither of light; I recently had an interview where the task was to deliver a presentation on something you are passionate about. This was an excellent task, although once I had started to research and compile ideas for mine, ten minutes felt far too short. I was just getting started! My topics of choice were either adventure or poetry or sustainability. Poetry felt like the longest standing relationship, so that’s what I chose. The piece below comprises a little of what I spoke about.

Poetry has always been been the murmuring elders in my ear, and the shape of ancestors guiding me on the peripheries.

First introduced to language at Hebrew School aged six; I learnt to read twisty shaped alphabet letters fluently but had no idea what they meant. With this separation, I was able to appreciate instead the lyrical lilt and tilt of the sounds and their cadence. How they tasted in my mouth and sounded in the air when I breathed them out. They formed a love affair with words that has continued ever since.

Poetry has always been there, in the whispers of the night.

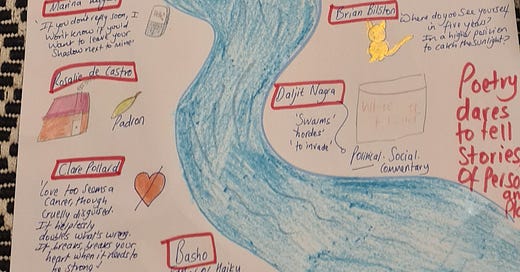

Around Year 3 at school, my first homework in primary school, that I can recall, was being asked to memorise a poem. Dad helped me choose Wordsworth’s ‘I wondered Lonely as a Cloud’:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

And with that I met poetry and we became instant friends.

It is often the lens through which I interpret the world. By knowing poetry and holding it in mind, it allows me to carry great beauty everywhere I go. On cycle rides, I have carried poetry in my handlebar bag and repeated memorable passages in times of struggle or joy. Ben Okri’s ‘To An English Friend in Africa’ holds some of my favourite words: ‘All that you are experiencing now will be moods of future joy so bless it all.’

I learnt about brevity through poetry, about capturing one image and clasping it in your palm like a butterfly, ready to lift its wings and fly.

Imagistic poetry is amongst my favourite and the Haiku form in particular, marked by its brevity of 5,7,5 syllables per line for 3 lines.

Poetry has been a keeper of truth in a world that often seems ridiculous; poetry ameliorates, it softens, it dares.

From William Carlos Williams in ‘This Is Just To Say’ he apologies (very half-heartedly) ‘I have eaten the plums that were in the refrigerator/ that you were probably saving/ forgive me/ they were delicious/ so sweet/ and so cold.’ I learnt that you could apologise through poetry and simultaneously be decidedly cheeky.

During my undergraduate days, I sat through university lectures of Shakespeare, Alexander Pope and Chaucer moving from the 13th century to today, and although I appreciated Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’, a hilarious text accounting for the pilgrimage of 29 characters as they amble from Southwark in South London to Canterbury in Kent, with bawdy, raucous, scandalous action along the way – what really made me perk up was when the era of modernism arrived, think 1930’s onwards, but I sat up even straighter in my chair when the contemporary poets marched into the room. I was lit up, electrified, convinced.

I have passed many happy hours listening to Padraig O’Tuama’s ‘Poetry unbound’ podcast, his lyrical Irish tones dissecting modern poems, a favourite being: ‘Someday I will Visit Hawk Mountain’ by M. Soledad Cabellero, that I loved. It speaks of his lack of knowledge about hawks and then, ironically goes into so much detail that you know his lack of is anything but. He writes how they ‘hang in the air like questions.’

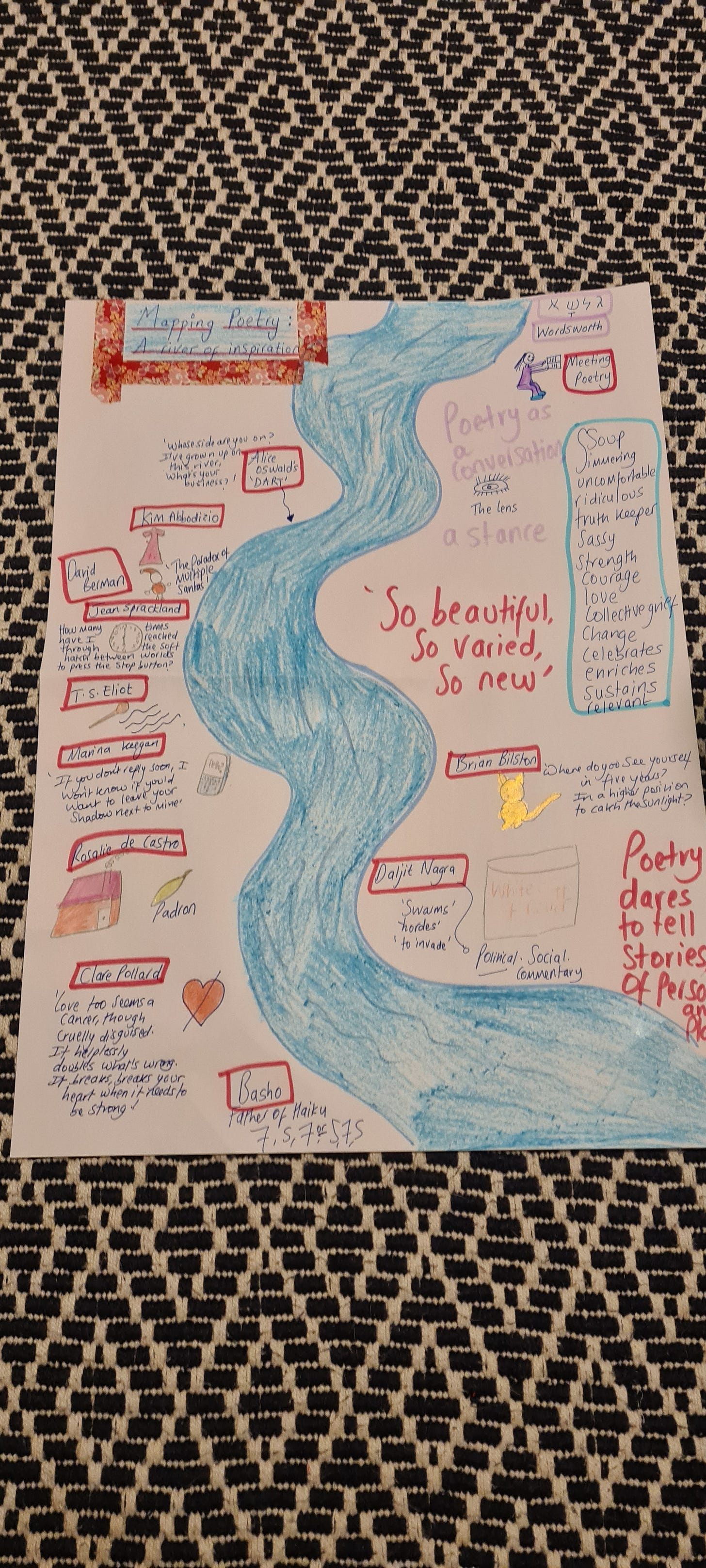

And I have been inspired and reminded at the relevance of poetry (and the shortness of time) by the voice of a young poet, Marina Keegan who tragically died aged twenty. She writes in her poem ‘Nuclear Spring’ in 2012 about phone usage, with such poignancy:

So what I’m trying to say is you should text me back.

Because there’s a precedent. Because there’s an urgency.

Because there’s a bedtime.

Because when the world ends I might not have my phone

Charged and

If you don’t respond soon,

I won’t know if you’d wanna leave your shadow next to mine.’

Poetry has helped me understand collective grief, in the stunning lines written by John Burnside after 9/11 in his poem ‘History’ whereby his narrator stands on the beach with his toddler son watching the army planes fly overhead near a Scottish airbase, aware of the news over the pond, of this tragedy and the incongruity of the beauty in front of him, yet still is able to be ‘attentive to the irredeemable.’

Poetry is relevant. It helps us understand culture. David Cameron’s comments about migrants ‘swarming’ the UK was captured by Daljit Nagra in the poem ‘Dover Beach’. Nagra’s poem is a powerful description and voice for the migrant arriving in a haze of stereotypes, or the second and third generation immigrants whose parents and grandparents changed everything to give them opportunity.

Nagra uses the epitaph from Matthew Arnold written in the 1800’s: ‘So Beautiful, So Varied, so New’ at the image of Britain and the white cliffs of Dover pop into view from a boat and the stale smell of diesel is heavy in the air. These triplet phrases continue to be three of my favourite clauses ever, so much so that they hum in my mind at random moments in life, an incredible moment in nature or just the knowledge of life and its possibility on a particularly optimistic day, wow, would you look at that, so beautiful, so varied, so new.

I am grateful to poetry for being the vehicle through which I travelled along the first turbulent year with a baby: the simmering, uncomfortable, ridiculous exhaustion, articulated in scribbled handwriting in the depths of night, leading to a collection of poetry produced when I felt the most societally, unproductive.

I learnt about sass and feminism and strength through Kim Abbodizio’s poem ‘What do Women Want?’

I want a red dress.

I want it flimsy and cheap…

I want it sleeveless and backless,

this dress, so no one has to guess

what’s underneath…

…When I find it,

I’ll pull that garment

from its hanger like I’m choosing a body

to carry me into this world, through

the birth-cries and the love-cries too,

and I’ll wear it like bones, like skin,

it’ll be the goddamned

dress they bury me in.

Poetry has played a part in helping me bring a favourite poem of Clare Pollard’s ‘The Caravan’ into the order of ceremonies for my friend’s wedding. It helped me celebrate my Dad’s 60th birthday with my own poem tugged together, weaving memories from our India trip together.

It has enriched my travels in the world, giving me a voice to always remember and relive time. As I hiked across Spain on a Camino one year, on reaching the verdant, green landscapes of Galicia, famous for the padron pepper, I chanced upon the museum and former house of the wonderful poetess Rosalie de Castro. Several hours passed with me immersed in her verse, translated from Galician into English.

My wild camping adventures began in Devon to the backdrop of a slim volume of Alice Oswald’s ‘Dart’ poem, where she lived by the river for a year recording the voices of those who lived and interacted with the water. Canoeists, farmers, labourers, thatchers, potters, children. I wild swam, hurling myself into that same river. It’s copper coloured water flashing on my freezing lily-white limbs and her words spinning around my ears, diaphonous.

Poetry has been an anchor, soothing. No wonder books such as ‘The Poetry Pharmacy’ have been created: a book for every type of healing and season from emotional, symptomatic to psychosomatic.

Poetry is sustaining during difficult times, especially the poetry of Mary Oliver ‘tell me about despair, yours and I will tell you mine.’

T.S. Eliot wrote such beautiful oddities of language in ‘The Love Song of J.Alfred. Prufrock’ that I have spent years turning over and languishing in them: ‘I have measured out my life in coffee spoons… I have heard the mermaids singing each to each./I do not think that they will sing to me./ We have lingered in the chambers of the sea/. By sea girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown/ Till human voices wake us, and we drown.’

I have circled back to these words and managed never to forget them.

I cannot turn off my own alarm clock without remembering Jean Sprackland’s poem ‘Alarm’ and her words: ‘How many times have I reached through the soft hatch between worlds to press the stop button?’ Poetry is the wallpaper of my mind, scrawled with the words and insights of a thousand others

.